Here are both episodes of Travel Thru History featuring Upstate New York. This week they aired “Buffalo/Niagara” and last week they aired “Albany/Saratoga” (I’m featured at the State Capitol segment starting at 14:30).

Here are both episodes of Travel Thru History featuring Upstate New York. This week they aired “Buffalo/Niagara” and last week they aired “Albany/Saratoga” (I’m featured at the State Capitol segment starting at 14:30).

Back in March I had the opportunity to work with Albany Mayor Kathy Sheehan’s Heritage Tourism Committee, where I drafted the first-ever guide solely dedicated to heritage sites in the city. Two weeks ago, the first edition was released. I may be biased, but their results look quite impressive.

I created the original layout, wrote almost all of the text, and introduced a number of other additions (QR codes, site hours in grid form, et cetera). After April, the Committee made their necessary revisions and brought in graphic artists to bring the project to life. You can download the entire booklet as a PDF here.

It was a challenge to organize 400 years of history succinctly, let alone provide directions to all the disparate sites. One of my suggestions was to map out not only the sites a tourist would visit but the great architecture they would see along the way. The back of the guide provides a way to find the city’s many buildings and sites on the National Register of Historic Places:

I even tried my hand at defining themes for the featured sites; an extra layer of info for visitors who are tight on time and have particular interests in mind. I hope Albany revisits and revises these themes as develops its heritage tourism strategy in future editions. Special thanks goes to all the people I worked with listed below.

Happy Halloween. . . . This story has been retold around Akron, New York, a village in the town of Newstead, over the last two centuries. Even the official website for Erie County has a variant of it online. The definitive tale is by Arthur C. Parker, who recounted it in The Life of General Ely S. Parker: Last Grand Sachem of the Iroquois. It was published by the Buffalo Historical Society in 1919; any more recent publication appears to derive from that source.

A professional historian and folklorist, Arthur was Ely’s great nephew and a Seneca Indian. He made the story part of the biography “for it was gossiped about the Parker fireside in the years of the early [18] ’30’s, and its dramatic incidents happened but a little way from their own doorstep. It is of importance, too, to those who live today, for it explains the ghosts that hover about the haunted corners.”

The below version of The Legend of Murder Creek was part of their 4th Grade local history curriculum at Akron Central School in the 1980s. I do not know who wrote it or if any other copies exist today, but it is definitely a direct adaptation of Parker’s book–even reusing the final sentence.

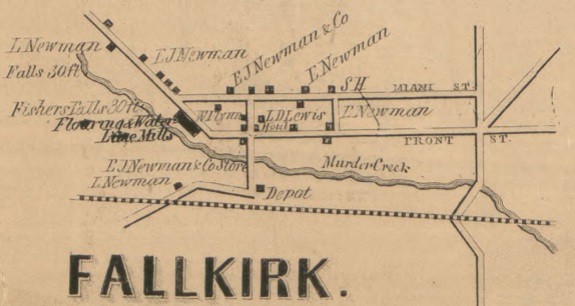

Akron Falls was known as Falkirk Falls for a time, and Falkirk a distinct settlement from Akron. This map from 1855 added an extra “L” to the name. East Avenue now runs along Murder Creek.

Murder Creek was originally known to the Indians as See-un-gut (roar of distant waters). This legend tells how the name was changed.

In the spring of 1820, a white man, named John Dolph came from Mohawk country near Utica and built his log cabin close to the See-un-gut. The creek attracted many settlers in those days because it was necessary to be near water as a source of power to operate mills. It was also important for the settler’s personal needs.

John Dolph and Peter Van Deventer had planned to build a sawmill on the Creek. One evening in October, John and his wife were discussing plans when they heard a shriek from the woods. John opened the door and saw an Indian girl running towards him breathlessly yelling, “Save me. Please save me!” John let her in his cabin and closed the door on a man on the outside yelling “Let me in!”

The Dolphs hid the girl and allowed the man in.

“My name is Sanders,” said the man, “and that girl is a prisoner, whom I am to take to authorities in Canada. Her father, a chief, placed her in my hands, because she wishes to marry a bad Indian.”

He looked around the cabin to see if he could find her. He couldn’t, and flew into a rage muttering, “She shall not escape, I will find her yet!” He then left the ca[b]in and hid himself in the woods.

Mr. and Mrs. Dolph then listened to the story of Ah-weh-hah’s (Wild Rose’s) life.

My home is near Spirit Lake, under the cliff about a mile below the Tonawanda Falls. My mother has been dead several years and my father, a chief of the Senecas, has just been murdered by Sanders. For more than a year, this dreadful man has been staying around Spirit Lake begging me to marry him. I love Toh-yon-oe (Gray Wolf) and will become his wife very soon. Sanders told me that rather than see me the wife of a Seneca, he would murder me and all who stood in his way.

My father and I were going to the Cattaraugus nation to avoid trouble. Gray Wolf was going to meet us there. We started out on foot, taking the old trail, leading to Te-os-ah-wah, a place called Buffalo by your people. When we reached the See-un-gut my father sat down to rest. Sanders came up behind us and said he was sorry for his past conduct. He wished me happiness in my life with Gray Wolf. The man spoke so nicely, he tricked us. When I turned to look eastward, I heard a blow strike and then a groan. Quickly I turned to see my father laying dead on the ground with Sanders standing over him with a club in his hands.

I fled into the forest with him close behind yelling he would kill me too. Here I am. You know the rest.

The Dolphs located Gray Wolf and informed him of the tragedy. He came to his sweetheart and together they journeyed to her father’s grave where John had buried him. They chanted the death song, as a last token of their affection. A grave fire was lighted and the sacred tobacco incense rose to life the burden of their prayer to the Maker of All.

Suddenly Sanders appeared from behind a tree. He and Gray Wolf struggled with knife and tomahawk until Sanders fell from losing too much blood. He was dead. Gray Wolf tried to speak to Wild Rose but instead staggered forward and fell. They had both died at her father’s graveside.

Mr. Dolph heard her cry. He found her on her knees sobbing the death chant. John then buried both bodies and comforted Wild Rose.

She often went to visit the graves of her father and sweetheart to chant her grief. One day the Dolphs missed her, they went out to the graveyard and found her lying upon the grave of Gray Wolf, dead of a broken heart. Beside the graves of her father and sweetheart she was buried.

As the legend goes ——- if you stroll along Murder Creek at midnight, you may hear the voices of the two lovers as they wander over the new dust on the ancient trail. Death united them in a bond the years have not broken.

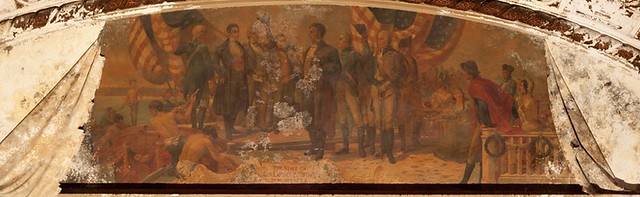

Samuel F.B. Morse, John Roebling, William Cullen Bryant, and Peter Stuyvesant (clockwise from top) on the Smith lobby ceiling

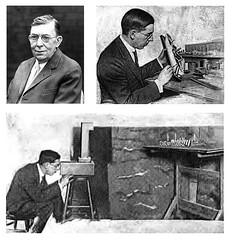

David C. Lithgow; from a 1978 edition of The Times Record.

David Cunningham Lithgow was born in Sheffield, England on 12 November 1868 but immigrated to the United States from Glasgow, Scotland as a young man, finally settling in the Capitol region in 1890. Some of his art depicts scenes of the Adirondacks, where he once had a cabin. Some family members believe he lived for a time on an Iroquois reservation and sketched many of its residents. Starting with odd jobs—draftsman for the Gilbert Car Works, drop painter at the Strand Theatre in Albany and Proctor’s in Troy—Lithgow became a nationally recognized artist. Some of his works include civic auditoriums in Cleveland, Ohio and Long Beach, California, and the courthouse in Elizabethtown. Lithgow lived at Hudson Avenue on Green Island until his death on 26 May 1958 at age 89.

Lithgow’s mural of Lafayette above Proctor’s Theater in Troy; from After the Final Curtain

Lithgow’s sculptures can be found throughout Albany, including the Spanish-American War Monument at Townsend Park and the St. Andrew’s Monument at Albany Rural Cemetery. Some of his other murals can still be found in financial institutions such as the Fleet Bank at State and Pearl Street, the State Bank of Albany, and the Cohoes Savings Bank. His most well-known murals, however, are probably the Iroquois paintings in the State Education Building.

William Andrew Mackay; from Camoupedia

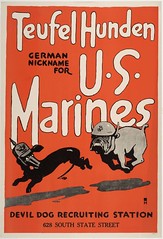

WWI propaganda by Charles B. Falls; image from Wikipedia

The Smith Lobby Ceiling Mural is attributed to Lithgow, but in the center panel, four small faces are painted next to three names: William Andrew Mackay, Louis J. Borgo, and Charles B. Falls. Mackay and Borgo also painted the ceiling of the State Office Building in Buffalo, and Falls was a professional illustrator. Interestingly, Falls developed propaganda posters during World War I, including some of the earliest uses of the “Devil Dog” by the Marines, while Mackay helped design camouflage for ships. This center section features four modes of transportation and commerce: trucking, flight, shipping, and locomotives.

The surrounding eight panels altogether depict the visages of thirty-two famous New Yorkers, from political leaders to explorers, scientists, engineers, inventors, artists, authors, and entrepreneurs. (Many of these faces in the Smith Building can also be found carved in the Great Western Staircase just across the street at the New York State Capitol.)

About a decade ago, Evergreene Architectural Arts restored the paintings in the lobby ceiling and several other rooms; this image comes from their website

A diagram of all the faces in the ceiling murals can be found by clicking here.

From 1933 to 1946, Lithgow worked on a series of fourteen murals at the Milne School in what is now the second floor of the Nelson A. Rockefeller College of Public Affairs and Policy at the University of Albany. It is no surprise that the themes he explored in those later murals—the Mohawk people, Albany as a trading port, and Henry Hudson’s 1609 voyage—reflect a long painting career accentuated by his projects on Capitol Hill. Those paintings are currently being restored. In fact, one of the University murals is of Capitol Hill itself, complete with an image of the Smith Building.

“1943–Capitol Hill–Modern Albany–Three Forms of Architecture” by Lithgow for the Milne School, now part of the University of Albany

Edwin W. Becker was born on 10 December 1912 in Brooklyn. He moved to the Albany area in the 1930s, eventually living on Nathaniel Boulevard in the suburb of Delmar, and enlisted in the Signal Corps during World War II. An employee of the New York State Department of Civil Service, he was an agency artist for four decades. The Civil Service Mural he completed in 1962 was located where he worked: the Harriman State Office Building Campus just outside the city. In 2006, when Civil Service workers relocated into the Alfred E. Smith State Office Building across from the State Capitol, they brought the mural with them. It has been on display in the Department’s reception room ever since.

Civil Service workers, from teacher to park ranger

The Civil Service Mural highlights New York’s movement from a “spoils system” of patronage to the modern merit system of today. Users of patronage—DeWitt Clinton, Martin Van Buren, and Thurlow Weed, for example—are shown next to important reformers such as Dorman B. Eaton, Elihu Root, Theodore Roosevelt, and Grover Cleveland. In the left background, one can see the Hudson River, Henry Hudson’s ship the Half Moon, Robert Fulton’s steamship the Clermont, and packet boats on the Erie Canal. On the right, different Civil Service occupations are represented by various figures in occupational garb.

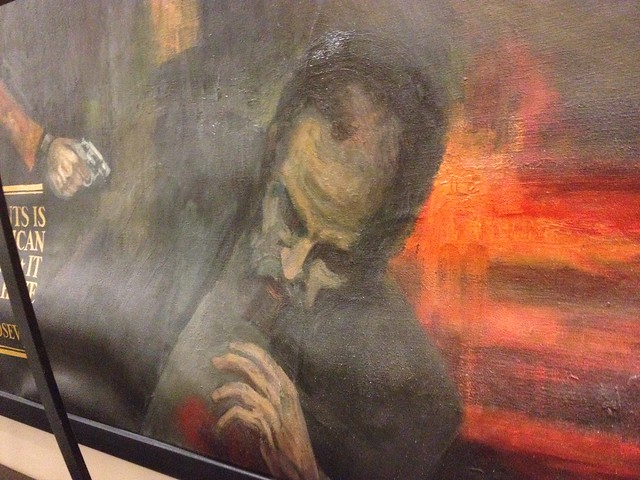

The killing of President Garfield

The most shocking feature of the mural reenacts a presidential assassination. Slightly left of center, the disgruntled patronage job seeker Charles Guiteau puts a bullet into James A. Garfield. The figures of several other men seem to watch as the shooting takes place, looking interested but unwilling to stop it. As listed by name at the end of this article, those men were politicians infamous for their use of patronage in political machines and opposing reforms. Though Vice President Chester A. Arthur had his own shady personal history with the spoils system, he made civil service reform the highlight of his short presidency. When he signed the Pendleton Act in 1882, it created a federal Civil Service Commission. New York was quick to make its own reforms, even instituting them directly into the State Constitution of 1894. President Arthur is buried in Albany Rural Cemetery.

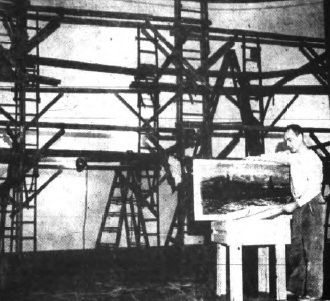

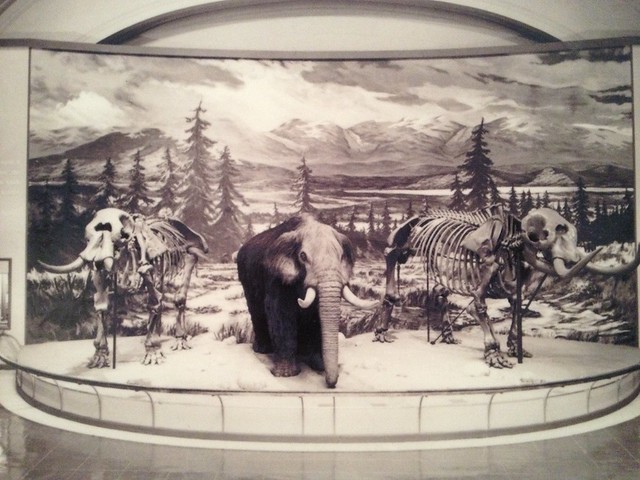

Mastodon mural on display c.1960. Historic photo from the current mastodon exhibit

Along with three other Delmar artists, Edwin Becker was part of a group called “The Village Four.” They held local art showings and contests in the 1950s and 1960s. The Albany Institute of History and Art exhibited some of his works as well, where he taught art classes in his spare time. Becker also painted murals for the mastodon display at the New York State Museum as seen in this black and white image from a 1957 issue of the Knickerbocker News. His 1960 mural depicting the history of Schenectady can still be seen in the First Niagara Bank on State Street in that city. Becker died on 6 February 1989 at the age of 76.

Becker’s Civil Service Mural

1 George Clinton

2 DeWitt Clinton

3 Martin Van Buren

4 Thurlow Weed

5 Thomas C. Platt

6 Roscoe Conkling

7 Charles Guiteau

8 James A. Garfield

9 Dorman B. Eaton

10 Charles William Curtis

11 Everett P. Wheeler

12 Grover Cleveland

13 Theodore Roosevelt

14 Horace White

15 Joseph Choate

16 Elihu Root

17 Civil service employees

This diagram, and more mural info, can be found at the NYS Civil Service website.

Back in 2009 I worked with filmmaker Diedie Weng on this documentary as part of Squeaky Wheel’s Channels program. Through this film, Diedie aimed to promote a conversation about low income communities’ efforts and struggles in revitalizing neglected historic Buffalo neighborhoods. It’s hard to believe the project began five years ago. Her efforts to film all those locations and edit all those interviews was an immense task, compounded by her living situation at the time. A Chinese national, she was living primarily in Toronto at the time, traveling between all three countries frequently.

Granted, my work mostly involved driving her to locations, procuring the right equipment, and other off-camera details. but it was still an eye-opening experience. Since Diedie was not from the city she had a fresh take on every place and person she saw. Probably a thousand people watched the film at the premiere night or online soon after. Later I took the film to presentations at libraries, classrooms, and community centers, and distributed dvds by request. At least five hundred more people watched the films through those “screenings.”

I think the film has held up remarkably well. There is nothing so unique about the problems being faced in Buffalo five years ago that cannot be understood by any city in America today. The recent Congress for the New Urbanism conference in the city tangibly articulated this. And issues in many of the places presented still persist: the bar being refurbished near the Central Terminal closed quickly, for example, and there is no new community museum in the Fruit Belt. The Market Arcade Film & Arts Centre, where the premiere and reception took place, will show its last movie tonight and close its doors.

One location where we did a lot of filming has shown an amazing transformation: the German Roman Catholic Orphan Home on Dodge Street. Below is a photo from BuffaloAH.com showing what the outside looked like.

Now I can admit that we swung around the back and entered through some loose boards. This photo from FixBuffalo shows the inside:

A smashed piano lay in pieces in the chapel, exposed in the darkness by holes in the roof. Down the hall, the floors were either covered in damaged tile or incredibly soft. I distinctly remember Diedie so concentrated on her camera that she did not realize the floor had given way right in front of her. Had I not warned her she would have fallen twelve feet right into the basement.

None of that footage made it into the film. Thankfully, the chapel and the adjoining building (seen above) is now part of St. Martin Village, a private redevelopment that uses part of the original campus as new housing. Click here to see a panoramic view on Google Maps. It’s not a perfect example of preservation but a sea change from what existed there half a decade prior.

An aunt recently passed away, and in her home a number of old photographs were rediscovered. My cousin Jasson Schrock of Heipile scanned the photos below, as well as many more.

My grandfather, Tobe Schrock, was stationed in Japan after World War II. He is the one on the right.

Tobe was trained as a paratrooper while in the Army.

Joseph “Dynamite Joe” Schrock was a grandfather of Tobe, living from 1836 to 1912. Tobe’s father–also Joseph–lived from 1872 until 1946, right when Tobe was about to leave for Japan.

The Schrock farm in Indiana

This photo is captioned “Ezra Lantz, his wife, and Emma Schrock.” Emma Schrock, left, was Joseph Schrock’s husband and lived from 1888 to 1989.

Tobe, Atlee, Perry, Alvin Schrock playing in the snow.

Schrocks eventually moved to Akron, New York. This silo used to be on the property until it went down from being too full.

Manley, Tom, Paul, Tommy, Jerry, Kathy, David, Shirley Cummings, 1956. According to my father Jerry, this “picture of everyone on the porch eating candy apples, was taken at the farm of Walter Host on Burdick Road. Walter was Fred’s and Jasson’s Great Grand Father [father to Tobe’s wife Margaret, Jerry’s mother].”

Shortly after my wedding just a couple months ago, a relative dropped off a box of personal photos collected by my grandmother who passed away three years ago. Not all photos were found with labels, and over time faces and places were forgotten. Some of the 1000 images go back to at least 1930. Below is a slideshow featuring just a fraction of the images I digitally scanned over a week’s time.

Catherine Taylor (born Catherine Euphemia Graham) was the child of Canadian missionaries who owned a home in Jasper, Ontario. She also lived in Egypt for a lengthy period of time during childhood–long enough to learn Arabic and get sick of the Pyramids, she recalled–and again doing her own missionary work as an adult. She also traveled Europe and the Middle East shortly after World War II. With training as a nurse and a schoolteacher, she eventually settled down on a farm in Cardinal, Ontario with my grandfather Charles.

Catherine Taylor (born Catherine Euphemia Graham) was the child of Canadian missionaries who owned a home in Jasper, Ontario. She also lived in Egypt for a lengthy period of time during childhood–long enough to learn Arabic and get sick of the Pyramids, she recalled–and again doing her own missionary work as an adult. She also traveled Europe and the Middle East shortly after World War II. With training as a nurse and a schoolteacher, she eventually settled down on a farm in Cardinal, Ontario with my grandfather Charles.

The collection is a fascinating look at a world that looks vaguely familiar to today, but not quite. Nations like Palestine, Transjordan, and West Germany don’t exist in the same way anymore. But then again, neither does Canada. . . .

Jennifer and I were married on Saturday. Photos may come later but I wanted to post some images of the centerpieces. They are custom laser etchings designed and produced by Sean Nowicki of BFLOMADE, with Jennifer’s input. Sean recently put up an Etsy page so people can contact him directly. Our centerpieces were a bit large but he can create 2-D and 3-D etchings of most anything in different sizes.

Jennifer and I were married on Saturday. Photos may come later but I wanted to post some images of the centerpieces. They are custom laser etchings designed and produced by Sean Nowicki of BFLOMADE, with Jennifer’s input. Sean recently put up an Etsy page so people can contact him directly. Our centerpieces were a bit large but he can create 2-D and 3-D etchings of most anything in different sizes.

The century-old Delaware Court is an elegant, unobtrusive building on the Chippewa Strip. The events that took place inside, however, changed the city forever. For decades, Delaware Court was a mecca for Buffalo’s most important architects as they built Buffalo’s most important buildings.

The Delaware Court Building, planned for demolition. Photo from September 2013

A much earlier photo with Delaware Court in background. From listing on Preservation Ready Sites

Delaware Court was designed by architects Lansing, Bley & Lyman and opened in 1917. Lawrence Bley hailed from nearby Hamburg, while Duane Lyman, once declared the “Dean of Western New York Architecture,” was originally from Lockport. Williams Lansing worked previously as a draftsman for the prolific Green & Wicks firm, then partnered with Green & Wicks draftsman Max Beierl to build landmarks such as the Connecticut Street Armory and St. Francis Xavier Church (now the Buffalo Religious Arts Center). Lansing, Bley & Lyman worked together for less than ten years and Delaware Court is one of their few remaining commissions. Still, they created some notable buildings, including the current President’s House for Buffalo State College on Lincoln Parkway. Lansing left the firm in 1919 to partner with Chester Oakley, but Lansing died a year later. Oakley continued until his own death in 1968, best known for a trinity of ornate Catholic Churches: St. John the Baptist, Blessed Trinity, and St. Casimir’s.

Minoru Yamasaki, lower left, and Duane Lyman, upper right, in 1963. Photo from Chris Brown

Bley & Lyman worked together for another two decades, designing the Saturn Club, building 800 West Ferry for Darwin R. Martin, and partnering with EB Green for what is now the Old Federal Courthouse on Niagara Square. When Bley died in 1939, Lyman carried on as Lyman & Associates until his passing in 1966. That firm supervised the addition to the Liberty Building, Minuro Yamasaki’s One M&T Plaza, and several buildings on the University of Buffalo’s South Campus. Like many later architects they used the Delaware Court location as a springboard for bigger and bigger opportunities.

Postcard of Rand Building at night

Delaware Court immediately attracted other architects as tenants. In 1917 architect William A. Kidd moved in with partner and brother Franklyn J. Kidd, where they remained until 1922. Their most well-known work from that period is probably the Rand House on Delaware Avenue’s “Millionaire’s Row.” Today the mansion is home to Canisius High School. Later, Kidd & Kidd would also design the Rand Building on Lafayette Square and assist Eliel & Eero Saarinen on the world-famous Kleinhans Music Hall on Symphony Circle.

After World War I, Delaware Court became a hive of activity. Buffalo’s booming population required the city to set aside $8 million for construction of not one but eighteen new public schools. Rather than compete for eighteen separate commissions, thirty-five architectural firms banded together to form Associated Buffalo Architects, Inc. and opened an office in Room 40 of Delaware Court. Individual firms would be given buildings but recognition would go to the ABA. Contracting directly with the Buffalo Board of Education, the entire project was put under the auspices of an internally chosen board of local architects. Duane Lyman was appointed Secretary.

A rendering of Intermediate School #11 by the Association of Buffalo Architects, designed by George Cary and located at Doat Street and Poplar Avenue. Cary was on the Board of Architects for the Pan-American Exposition of 1901 and designed the Buffalo History Museum.

“It will no doubt come as a shock . . . to learn that fifty architects in the city of Buffalo consented to have seven of their number pass judgement on their professional qualifications,” noted the Journal of the American Institute of Architects. The Engineering News Record called the association “A very striking example of disinterested service to the public by a group of professional men–the most striking we can recall in the construction professions.” Contractors could still bid on specific construction projects through the BoE, but blueprints and other plans were only available through the Delaware Court office.

A rendering of Intermediate School #2 by the Association of Buffalo Architects, designed by Esenwein & Johnson (closed in 1961 and later demolished). Esenwein & Johnson are best known for the Electric Tower, the Calumet Building, and Lafayette High School.

Even more notable, the association brought in the nationally renowned William B. Ittner of St. Louis as Consulting Architect for all school designs. Ittner promoted a general “E” formation of central schools throughout the country, using distanced wings for subject-specific classrooms and labs and a middle third wing for gymnasium, auditorium, and cafeteria use. If you attended a school built between World War I and World War II you were probably in some version of an “E” plan school, and the man who popularized it worked out of Delaware Court. This format was used in cities as well as rural schools, as the era of one-room schoolhouses subsided in favor of central school districts around this time. Ittner’s push for orderly and efficient school plants was promoted in earnest with the aid of the Department of the Interior. The “E” type is probably the most ubiquitous public architecture in American history. ABA no longer exists, but Ittner’s firm established in 1899 still creates schools.

Buffalo City Hall under construction. Photo from Library of Congress

In 1926 the new firm of Dietel & Wade moved into Delaware Court. For the next five years, plans for one of the biggest buildings of its kind in the nation came out of their office. While at Delaware and Chippewa they designed and oversaw the construction of Buffalo City Hall–one of the premier examples of Art Deco anywhere. Architect John Wade brought in extra staff including his mentor, Sullivan W. Jones, to assist on the large project. Jones was simultaneously the State Architect under Governor Al Smith. (One of the few remaining buildings by George Dietel, the St. Francis de Sales church in Hamlin Park, is currently for sale.)

National Gypsum Company headquarters on Delaware Avenue. Photo from WNY Heritage

Like Duane Lyman, Frederick C. Backus was a veteran of World War I; he worked as a draftsman for Bley & Lyman for a time. At one point Backus was also Buffalo’s City Architect before striking out on his own, and the City Architect’s office is where he found draftsman Donald Love. Backus originally hired David Crane, who worked in EB Green’s office, as his personal draftsman in 1936 but elevated him to partner. Love would take leave during World War II but would return after being wounded in battle. Backus, Crane & Love remained in Delaware Court into the 1960s and were trailblazers for Buffalo’s modernist, post-war construction period. They designed major projects including Erie County’s Rath Building, the Marine Drive Apartments, and the National Gypsum Company Building.

Willert Park Courts. Photo from the Library of Congress

Backus, Crane & Love’s most historic accomplishment–like the Delaware Court building where it was conceived–is under threat of demolition. The Willert Park Courts, the first public housing open to African-Americans in Buffalo, began construction in 1939. A WPA project, the first phase consisted of 172 apartments. For years it was the only public housing for the city’s African-Americans, and it remains a cultural landmark for generations of residents to this day. Walls and private entrances still exhibit unique sculptures by Depression-era artists Robert Cronbach and Harold Ambellan. In 1940, the Museum of Modern Art in New York City published a Guide to Modern Architecture featuring the most vital modern buildings of the 20th century. MoMA highlighted Willert Park alongside Louis Sullivan & Dankmar Adler’s Guaranty Building and commissions by Frank Lloyd Wright as Buffalo’s best examples of modern design.

The office of Backus, Crane & Love in Delaware Court c.1946. Photo from American Institute of Architects

Delaware Court’s convenient location for networking, its large windows able to flood sunlight onto drafting tables, and an attractive, classically designed facade (as if to advertise “Professional Architects Inside”) are all reasons why it became a mecca for Buffalo architects. Recent hotel development plans for the property involve complete demolition of the building and the removal of all tenants. New construction, however, would mimic the curved corner entrance. Developers have hinted as preserving pieces of terra cotta decoration but those plans appear tenuous at best. Toronto’s Allen Lambert Galleria in Brookfield Place comes immediately to mind as an example of how older buildings can be woven into new construction if an inspired architect is involved. One wonders what a Duane Lyman, John Wade, or Frederick Backus would design for the property if they were alive today. . . .

Proposed new building for Delaware Court Site. Image from Buffalo Rising.

Thanks to Jennifer Walkowski for some of the information in this post.